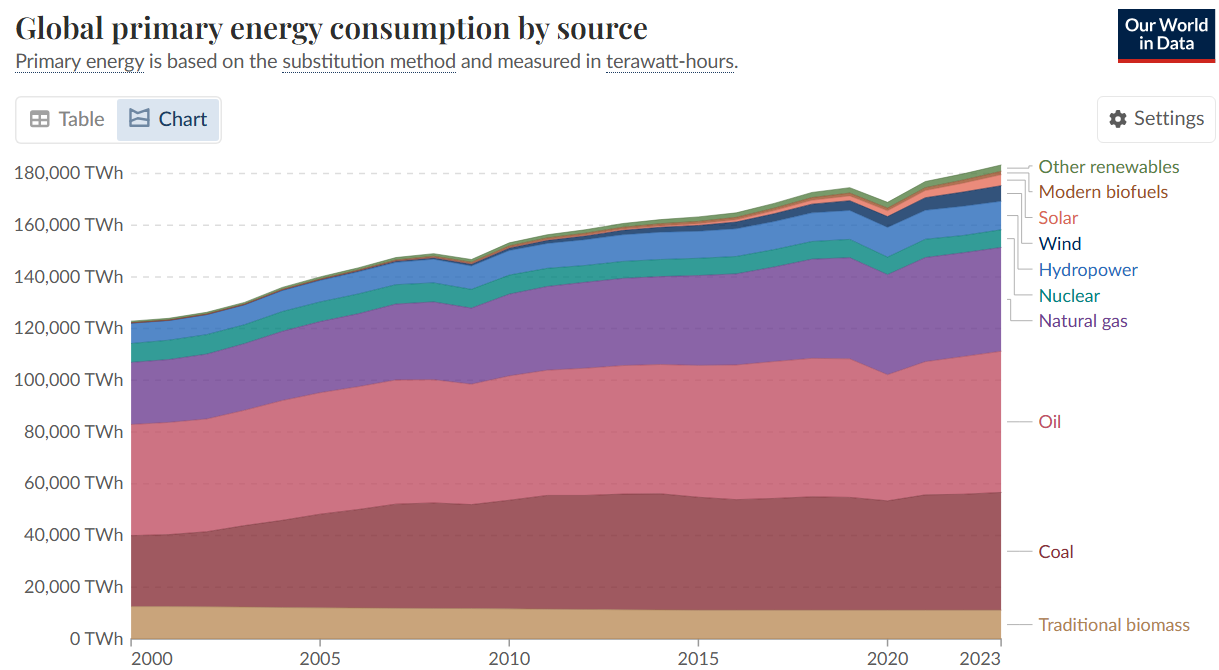

Here’s an interesting graph of the world’s energy consumption by source.1 What I find fascinating is that no source is being reduced. Instead we have additional sources added to the set so we can get evermore power.

The biggest example? Traditional biomass is wood. Yep, we’re still burning as much wood now as we did in 1800. Wood has not been replaced, we’ve just added capacity with additional sources.

And the last 23 years to drill into the addition of renewables

Coal looks to have leveled off. So if we continue in the theme of the last 2 centuries then coal will hit steady-state as wood did when we started adding coal to the mix in 1800. Not reduce but level off.

What we’re trying to do in reducing hydrocarbons is something we’ve never accomplished, reduce the use of an existing energy source. We haven’t been able to reduce burning wood and we’re now trying to reduce that as well as coal, oil, & gas.

This is not to say it can’t be done. The car has mostly replaced the horse.2 And we need to do it if we’re not going to cook our planet. But not having reduced wood burning over the last 200 years illustrates how bloody hard this will be.

This also illustrates how small a part of the energy picture consists of renewables. Hydro, which has barely grown in the last several decades, is still larger than wind plus solar combined. And nuclear also has shown no growth over the last several decades. Nuclear is smaller than wood.

Reducing Hydrocarbons

First off the history of wood as a source should give us the humility to realize we’re not going to eliminate hydrocarbon use. Not in the immediate future. It’ll be a giant struggle to first level off oil and gas and then to start reducing coal, oil, & gas.

Second all three hydrocarbons each are larger than every other source combined. We need to focus our efforts. That means reduce first coal,3 then oil,4 and only then gas. And this needs to be addressed worldwide.

So let’s say we have a magic wand and can instantly conjure up the generators we need to power the world. The average power generated in the world is somewhere in the range 2.7TW - 4.6TW. Best number I found is 3.4TW5 so we’ll use that. How many generators will this require?6

Batteries - Lots & Lots of Batteries

For nuclear if you have those plants, we’re done. If all are sited where the hydrocarbon plants were we’ve even got the transmission lines built out. We just move the line terminus over 500 feet.

But for wind & solar there’s a giant expense - batteries. For a primarily solar solution you need to power the grid and charge batteries for 6 hours/day7 and then use those batteries to power the grid for 18 hours/day.

Then for both wind & solar you need batteries for bad weather. Low winds, overcast skies, etc. If you have no hydrocarbon backup, you may need enough batteries to provide power for over a week. People are not going to like on day 8 of bad weather being told no power until the weather improves. If it’s a winter storm people would die in that case.

In this case you need to overbuild the wind/solar generation. Say it needs to handle 3 day storms and those come at most every 12 days. That requires a 25% overbuild to charge up the 3 day batteries over the 12 days after a storm.

On the flip side you can keep the entire hydrocarbon generating infrastructure up and running. If you only need it 5% of the time, then great success of reducing CO₂ emissions. But we retain the giant expense of maintaining the system of mining the hydrocarbons, transporting them, and then burning them in a turbine.

You can ameliorate some of the extra batteries with transmission lines. But first off we’re talking significant capacity to power all of one region of the U.S. from another. That will be very expensive. And weather tends to be regional so it means pulling an immense amount of power from one region to another. And that requires overbuilding of the wind/solar generation.

Reliability

Resilience/reliability almost certainly means, for wind/solar, keeping the existing hydrocarbon generating system up and running. There’s no number of batteries and additional transmission lines where I think we’ll be able to say - that can handle any weather combination.8

On the plus side for leaving the hydrocarbon generation system in operation, having it handle the worst 5% of weather cases, that will reduce the number of batteries needed significantly. Battery sizing becomes a question of trade-offs instead of life & death.

And so…

Reducing the use of an energy source is ridiculously hard, incredibly expensive, and probably the biggest job the human race has undertaken. We need to do this, but our only chance of success is to find the most efficient/effective solution.

And cost effective. People are not willing to pay significantly higher electric bills to reduce carbon emissions.9 They should be willing to. They should be highly in favor of doing so. But they aren’t. So this needs to be solved with that constraint.

The best solution is almost certainly a combination of sources, not solely one. And there are other possibilities like geothermal that could also be part of it. But I think it helps to understand the scope of the problem to know just how many units of each type addressing this will require.

As a work animal.

Coal not only emits more CO2 per GW than oil/gas, but it also emits a lot of other poisons.

Oil is not environmentally worse than gas, but politically it is based on the producing countries for each.

All numbers from OpenAI o3-mini. I ran this also using Gemini & Qwen and then checked the citations from all three. There’s a range of numbers from various sources and the OpenAI ones were near the middle of the ranges.

This is average and electricity is not constant over the day or year. Peak power tends to be as much as 2.5 times baseload power. This is addressed with a combination of storage and peaker plants.

The sun is up for more than 6 hours. But when it is low it generates less electricity. So solar tends to be effectively 6 hours of the sun directly overhead and 18 hours of darkness.

If you have electric heat and it’s a giant snowstorm outside with temperatures below zero - reliable electricity is life.

Most surveys show people are willing to have their utility bills increase $200/year to combat climate change, no more. The voters in Germany and the UK are showing what happens when it increases beyond that.

I'll give you an idea for a column.

1) Electricity costs around $50/mwh. The comes to $0.05/kwh, which is a solid wholesale price for electricity, which will sell to the consumer for $0.15/kwh.

2) Large scale storage batteries will cycle once per day.

3) the current cost for the batteries is $120/kwh. That is $120,000/MWh. The battery will last 20 years. It will be cycled around 7,500 times. So, it costs $16 per cycle.

4) The $50/mwh is what it costs to generate the power, so the $16 per cycle is added to the $50/mwh. You also lose power in storage, about 10%.

5) That means your power costs, from the battery will be about $70/mwh. That gets you to $0.21/kwh to the consumer, a 50% price hike.

6) That assumes of course you cycle once per day, but as wind and solar add more and more battery capacity, what if you assume the battery cycles every 3 days? Every 10 days? How about once a year? That $0.21/kwh starts ballooning up very rapidly.

7) Again, this is over and above other management charges added to handle an unstable grid.

Picking a nit: coal is not a hydrocarbon. It's just carbon.